Thursday, December 24, 2009

New books by post!

I mean...namaskar!

I'm very excited at the moment because two books have just arrived in the mail: Dreaming in Hindi by Katherine Russel Rich and How Much Should a Person Consume?: Environmentalism in India and the United States by Ramachandra Guha.

Oh my goodness. First of all, these books are just so beautiful - smooth, unfurled pages, colorful, unstained covers, and just the right weight and thickness to prop my eyelids open on a rainy (or snowy, as the case may be these days) afternoon. I bought them new, which I rarely ever do with books. My knowledge of the Indian subcontinent, up until this very moment, has come from outdated National Geographics, scuffed-up copies of the Mahabharata, and snippets of Al-Jazeera on CNN (which is, of course, the most enthralling news channel on the planet.)

Hey, I suppose it's one step closer to a plane ticket.

Awhile back I read (and reviewed) Elizabeth Gilbert's Eat, Pray, Love. I was so disappointed in that book. Gilbert had traveled to India on a whimsical soul search, but everything about her spiritual journey smacked of ethnocentric mockery and slack-jawed gaping at Indian "weirdness" (though to be fair, I believe it was unintentional - and I am probably biased). Though Dreaming in Hindi by Katherine Russel Rich is yet another American travel experience, I have a good feeling about this one. Rather than imitating Gilbert's desire to escape from worldly concerns and commune with God, Rich throws herself into a frighteningly foreign throng in order to understand the most rudimentary building block of human experience: language. In a "rash" moment, Rich moves to Udaipur to learn Hindi, and her memoir details the unexpected lessons she learns through it. I am really excited to delve into this one, mainly because my own experiences in learning Hindi so far have been incredibly transformative.

What started out as an innocent curiosity has tried my patience more times than I can count - but I always remind myself that the joy of learning Hindi is that it isn't easy. Every new word is so abstract from the limitations of my English-speaking mind, sometimes even one new sound, one new arrangement of a sentence, can open up a whole new world inside my mind. To me, these are not just words. These are Lilliputian victories; the foundational blocks of a seemingly alternate universe. And through this foreign lens I have come to understand my own language, my own country, and my own people better. That's why I'm always eager to share what I'm learning about India with the people that I meet.

I once met a man from Ethiopia while traveling on a bus from Boston to New York City. He was just CRAZY for America. He told me a great and epic love story, from his beginnings on a small farm growing up with eleven brothers and sisters in Ethiopia to his struggle to survive on the streets of New York City. He had fought for America in such a way that I had never heard before. He was proud of where he came from, where he was going, and where he was. He was simply happy to be alive. After he got off the bus and we went our separate ways, I never looked at life in quite the same way again.

So maybe I'm a little crazy too, but I really can't wait to review this book for you guys. Maybe I can't convince you to start learning Hindi, but I want you to know how much joy there is to be had in the experience if you're willing to seize it.

Oh, boy. I'm beginning to sound like a high school math teacher. Moving on.

How Much Should a Person Consume?: Environmentalism in India and the United States by Ramachandra Guha jumped out at me from its, er, "shelf" at Amazon.com because of its obviously unique approach to this hot-button issue. In some of my previous posts I explored the differences in agriculture between India and the United States, and what the water crisis really means to a country in which half of its hospital patients typically suffer from water-borne diseases on any given day. Based on research conducted over two decades, Guha's book plunges into the differences between environmental philosophies in India and America and arrives at a new "social ecology" approach to conservation, critically important to the relationship between these two great democracies and to the future of the world. It seems to be written in a friendly lilt, an approachable read for anyone interested.

Anyway, that's enough for now. I'll post my reviews soon enough.

Sunday, December 20, 2009

A Bengali Wedding.

"Weddings are big events here - festivities can go on for days. Marriages are most often arranged and set at an astrologically auspicious time, such as this wedding parade set after the full moon. Before sunrise I could already hear things getting started with the neighbors, whose son will be wedded."

"Weddings are big events here - festivities can go on for days. Marriages are most often arranged and set at an astrologically auspicious time, such as this wedding parade set after the full moon. Before sunrise I could already hear things getting started with the neighbors, whose son will be wedded."

"Before the bride makes her entrance, the groom and his family make preparations for worship in the temple. The crowd was very joyful and it was a real Bengali party, even though the strongest drink you'd find in this group of Vaishnavas would be a straight glass of Sprite."

"Before the bride makes her entrance, the groom and his family make preparations for worship in the temple. The crowd was very joyful and it was a real Bengali party, even though the strongest drink you'd find in this group of Vaishnavas would be a straight glass of Sprite."

"I got a sneak preview of the bride-to-be upstairs in her father's house. Ordinarily she is a somewhat plain, plump young lady, but here she is dressed so ornamentally and so radiant with happiness that she looks like a gandharva, or angel."

"I got a sneak preview of the bride-to-be upstairs in her father's house. Ordinarily she is a somewhat plain, plump young lady, but here she is dressed so ornamentally and so radiant with happiness that she looks like a gandharva, or angel." "The bride meets the groom for the first time. She covers her face with betel leaves to symbolize the humbling effect of her husband's presence."

"The bride meets the groom for the first time. She covers her face with betel leaves to symbolize the humbling effect of her husband's presence."

"Two of the bride's brothers lift her and circumambulate around the groom. She pelts flower petals at her husband-to-be, and his friends must dart in to 'shield' him from her love."

"Two of the bride's brothers lift her and circumambulate around the groom. She pelts flower petals at her husband-to-be, and his friends must dart in to 'shield' him from her love."  "A cloth is placed over the couple's heads and their eyes meet for the first time...in private."

"A cloth is placed over the couple's heads and their eyes meet for the first time...in private." "Now everybody else gets a sneak peek, too!"

"Now everybody else gets a sneak peek, too!"

"After the pandit offers a prayer to the elephant god Ganesh, he puts a coin and a spot of mehendi in the groom's right hand. The couple's hands are united with auspicious substances such as sweet grass, purified water and strings of flowers. This ritual is called panigrahana hathlewa."

"After the pandit offers a prayer to the elephant god Ganesh, he puts a coin and a spot of mehendi in the groom's right hand. The couple's hands are united with auspicious substances such as sweet grass, purified water and strings of flowers. This ritual is called panigrahana hathlewa."

"Now the father adds his hand in a gesture of blessing, giving his lovely daughter away."

"Now the father adds his hand in a gesture of blessing, giving his lovely daughter away."

"If you’ve ever wondered where the expression 'tying the knot' came from, it probably came from Hindu ceremonies in which the bride and groom’s clothes are literally knotted together for the rest of the night. The Vedas say that there is a knot in the heart caused by the false ego which thinks 'I' and 'mine' separately from its Creator, and when a man and woman are united the knot in the heart tightens. One thinks, 'I am this body. This is my wife, my family, my country, my religion,' and so on. But if a man and woman unite for the purpose of serving Krishna, they can work cooperatively to undo the illusion of material existence and thus progress spiritually. Then one thinks, 'I am servant of the Lord. Everything belongs to Him. Let me utilize it properly by engaging it in His service.'"

"Here, the bride and groom await the lighting of the sacrificial fire. They took half an hour to recite their vows, which they wrote up themselves and included things like 'always respect each other' and 'no domestic violence'. That's the unfortunate thing about Indian weddings. They take forever. There are a few more rituals after this, but the ceremony had already gone on for four hours, so I made my exit."

"Here, the bride and groom await the lighting of the sacrificial fire. They took half an hour to recite their vows, which they wrote up themselves and included things like 'always respect each other' and 'no domestic violence'. That's the unfortunate thing about Indian weddings. They take forever. There are a few more rituals after this, but the ceremony had already gone on for four hours, so I made my exit."Four hours? That's completely understandable. This post was getting a little picture-heavy anyway. Thank you, darling Devi!

Stay tuned!

I haven't abandoned this blog! Don't let yourself think that even for a minute. I've just been very busy this month preparing for examns (yes, that's an n), but I think my hard work has paid off. So far I've earned 18 college credits this semester with a 3.835 GPA - though that doesn't include the grade on my final math exam, which was all calculus. (Believe me, I should've taken Algebra.) I have a feeling my GPA will drop a little once I see the results on that...aahe.

Anyway, there's so much I have to share with you this month, so stay tuned!

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

Hindi Words of Arabic Origin

अदब (adab) – good manners

आदत (adat) – custom; tradition

ऐना (aina) - eye

ऐनक (ainak) – glasses (from Arabic أين)

अजीब (ajib) – strange

अक्ल (akl) – intellect (from Arabic عقل)

आलम (alam) – the universe

अलीम (alim) – learned

आशिक (ashik) – lover (from Arabic عشيق)

अजं (azam) – great (as in ‘मुग़ल इ अजं’, great Mughal empire)

अजमत (azmat) - greatness

अज़ीज़ (aziz) – dear; अजिजी is a girls’ name

दुनिया (duniya) – world (not in the geographic sense)

कसम (kasam) – promise

वक़्त (waqt) – time

सब्र (sabr) - patience

जन्नत (jannat) - heaven

मुसाफिर (musafir) – traveler

मुश्कील, मुसीबत (mushkil, musiibat) – problem

आमिर (amir) – rich

शहीद, कुर्बानी (shaheed, qurbaani) – sacrifice

इंसान (insaan) – man

जिस्म (jism) – body

ख्याल (khayal) – hopes; dreams, i.e. “I Had a Dream” by Martin Luther King

माफ़ (maaf) – forgive

हवा (hawa) – wind; air

अलीम (alim) – scientist

ग़म (gham) – a sort of pain; sadness

बस (bas) – enough! That’s it!

इन्तिज़ार (intizaar) – to wait

काफी (kaphi) – enough, sufficient

मदद (madad) – help

मोहबत (mohabbat) – love; a general context

इश्क (ishq) – love between two people

महबूबा (mehbooba) – my lover

ग़लत (galat) – wrong; i.e. क्या ग़लत है?; What’s wrong?

सवाल (sawal) – question

जवाब (jawab) – answer

दिमाघ (dimagh) – brain

मतलब (matlab) – asking for something (from Arabic تالاب)

किताब (kitab) – book

मौज्रिम (moojrim) - criminal

इशारा (isharaa) – a sign

कुर्सी (kursi) – chair

दौकने (doukane) - store

हकीकत (hakikat) – the truth

इन्सान (insaan) – a person; human being

यानि (yani) – meaning [that]… (a common sentence-filler like ‘um’, ‘yeah’, or ‘well…’)

A Lesson in Learning Hindi Through English

Some common words:

Anaconda – from Sinhalese henakandaya, “whip snake”

Bandana – from Bandhna, “to tie a scarf around the head”

Bangle – from Baangri, a type of bracelet

Bungalow – from Banglaa, lit. “a Bengali house”

Candy – from Sanskrit khanda, “sugar”

Cashmere – from Kashmir, the Himalayan state in India where wool is from

Cheetah – from c’itaa, “speckled”

Cot – from Khat, a portable bed

Cushy – from khushi, “happy, soft, comfortable”

Himalaya – from himalayah, “place of snow”

Indigo – from the Indus river; a tropical pea plant that can be used to make dark blue dye

Jungle – from jangal, “forest”

Khaki – “dust colored”

Loot – from luta, meaning “to steal”

Mango – from Malay manga or Tamil manaky, a fruit

Mongol – from Mughal, an Indian emperor

Mugger – from magar, meaning “crocodile”

Orange – from niranj, “orange”

Pariah – from pariah, an untouchable Tamil caste

Pundit – from pandit, an educated person

Sentry – from santri, “armed guard”

Shampoo – from champoo, “to massage”; i.e. to massage the scalp

Swastika – originally an Indian symbol denoting good luck. From svastika, “well-being”

Thug – from thag, “thief”

Dhadkan Oct./Nov. Issue Released!

A Harvest of Water - Nov. 2009 National Geographic

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/2009/11/india-rain/corbett-text

पानी के पॉवर - Pani ke Power?

It has been said the next war will be fought over water, the liquid natural resource that covers seventy percent of the earth’s surface. And why not? We often overlook the intrinsic power that water has over us – without it, life cannot exist.

For us humans, though, we need fresh water – which only makes up two percent of the earth’s total available water, and even most of that is frozen in glaciers or underground.

You can see, then, why wasting it could be a problem.

The most accessible source of freshwater is underground. We use diesel pumps to extract the water fairly cheaply for use in the home, and also for irrigation of crops. The Midwest consumes the most groundwater for agriculture; most notably to produce corn, which is then used to feed cattle – they fetch a better price after butchering.

The problem is that we are pumping the water too fast. We have to wait for rains to replenish the source, but not only is rain an unpredictable faucet, but even with rainfall it is becoming progressively more and more difficult for water to be re-absorbed into the ground. Why? Well frankly, there’s little ground left. It has been covered with cement, tar, houses, parking lots, buildings, you name it.

(Thought: What would happen if we stopped eating beef?)

The consequences of a shortage of water are even direr for the poor. In India, the cost of women fetching water is equivalent to a national loss of Rs 1000 Crore, or approximately $214 million.

In a country where most people make less than two dollars a day, $214 million is an enormous sum. As if such an injustice weren’t enough, 1.8 million children die each year from diarrhea – 4,900 deaths per day. At any given time, nearly half the hospital patients in India are suffering from water-related diseases. Worst, people living in the slums often pay 5-10 times more for water than do wealthier Indians living in the same city.

What can be done?

A new crop is on the market: rainwater harvesting. By capturing the runoff from buildings and sculpting the landscape to slow the flow of rain, we can ensure that we are collecting the water rather than wasting it. The water can then be used directly to refill empty tanks.

By installing water pipes on rooftops, in tanks or underground wells, urban families can conserve water while rural farmers can plant trees and create barriers on slopes to make the most of this precious resource.

“I think the simplicity of rainwater harvesting has made the water crisis much more approachable as a whole,” says Sweta P., a student in Udaipur. “When people feel daunted by new things, they tend not to get involved, but when the task seems to be fairly simple, their involvement level rises.”

“When I see people wasting water, it makes me really angry,” says Marttanda G., an economics student in Guwahati. “People here know there is a shortage of water. They see their neighbors suffering, but they still waste it.”

How can we reach out to people?

“People think the government will fix it; they have all the power. It’s so hard to make them realize that the government hasn’t – and won’t – do anything,” Sweta explains. “And even if they ever do, people will be dying of thirst by then.”

“Groups don’t understand,” says Marttanda. “But if you talk to an individual, you can explain the process to them, answer their questions. Really have a conversation. If they’re interested, they will tell others and the information will get passed on anyway.”

Though the shortage of water affects people in rural areas most harshly, it is those in cities that waste the most. Laws are being passed that require water pipes to be installed in urban homes and buildings.

Who knows? With heightened awareness and action, there may be a chance of having water for everyone in the years to come.

Shikshantar – The Peoples’ Institute for Rethinking Education and Development

Remind me again why I go to school for an Art History class that costs $270 (not including the textbook, which the professor reads from verbatim anyway) when I could spend 25 cents to go and see the real things?

Drilling an ‘artist’s vocabulary’ into our heads becomes utterly unnecessary when you walk through the exhibits; the words come as naturally as the works are striking. The contemplative restraint and repose of medieval art is plainly demonstrated by a man that seems to sigh while getting his eyes gouged out in an intricate relief altarpiece by Embriachi, while Jean Cornu’s Renaissance-era Venus Giving Arms to Aeneas’ sweeping melodrama pulls you in so closely, that if you’re not careful you might set off an alarm.

Oops.

(To be fair, I don’t think that even Jesus, or the Buddha, or whoever, could have resisted touching these sculptures. Maybe for a little while, sure – even I could do that. But lock them up, alone, in the museum for ten days, and you see what happens. They’re like hot stoves to children – burning with energy and simply begging to be touched. I swear, if you step close enough, these things defy the first law of thermodynamics.)

Someone please explain, exactly, why I need somebody else to evaluate, on a scale of 0-100, whether or not I am sufficiently appreciating art (as if that’s a valid thing to judge anyone for in the first place), but especially when that ‘art’ is just two-dimensional pictures in a book? Since when can x-number of credit hours honestly and accurately determined how much worthwhile knowledge I have gained?

And I’m not the only one to feel this way.

“There is so much pressure on engineering here,” says Sagar, an engineering student in Bangalore. “It’s considered by most to be ‘the best thing’ to do. If someone were to take up the pure sciences, or architecture, or the arts (God forbid), then people begin to think he has done so only because he isn’t meritorious enough for engineering. And in engineering again, there are these ridiculous notions. Computer or Electronics Engineering is considered to be the most prestigious. Almost everyone wants to do it, without the slightest idea as to what it really is, or what it means for them. And people inwardly sigh if you tell them you’re doing Chemical Engineering, or Metallurgy.

There are so many people here who are so unimaginably narrow-minded that think if they do well at college, or get some rank, they are successful in life. Outside school, they don’t exist. They have no hobbies; they are indifferent to so many issues. Here, in India, if you can learn the textbook by heart, you can secure a one hundred percent in your exams. And that’s the ‘successful’ everybody wants to see. It’s pathetic.”

In a country that desperately needs the creativity of its citizens to come together and craft solutions to its infinitely complex problems, it seems a crime to standardize education and the definition of ‘success’.

So when fourteen friends got together and decided to take a cycling yaatra (यात्रा - journey) around the city of Udaipur, Rajasthan for one week in order to reclaim the freedom of their education, it was a revolutionary gesture. How could these students, mostly from middle-class homes, be rebelling against a ‘privilege’ that is such a precious commodity to lower-class Indians?

The first tenet of the Shikshantar movement addresses the question bluntly: rather than being an escape from impoverishment, the formal education system is a means of stratification between the educated and the uneducated; it perpetuates inequality by labeling, sorting, and ranking human beings. It propagates the viewpoint that diversity is an obstacle, which must be removed rather than utilized if society wishes to progress. Schooling confines the motivation for learning to a superficial reward system, and disconnects knowledge from practical wisdom and living experiences.

Formal education privileges literacy in a few elite languages and degrades human expression and creation in other tongues. It causes people to distrust their native languages while relying upon newspapers, TV and radio for reliable information. It not only limits the scope of knowledge, then, but also reduces the sphere of opportunities for learning through abstract barriers (such as culture and language) but also physically (by institutionalizing education.) It invalidates learning experiences outside the four walls of the schoolhouse and of the English language. It degrades the dignity of labor; the learning that takes place through day-to-day experience and physical work.

It artificially separates human rationality and human emotion, inhibiting the sensitivity and aesthetic sensibility needed for creative output. Feelings are eschewed as inappropriate at times when they could actually be used as motivation and valuable tools for progress. Arguably the worst effect, it disintegrates the intergenerational bonds of families and communities, causing people to increasingly rely upon the government, science and technology, and the global market for their sense of identity, livelihood and self-worth. It exploits people, nature, and knowledge on a market of buy-sell relationships.

The students combated this by using the world as their classroom a week. They carried no money and refused to engage in monetary transactions; they didn’t eat without an honest day’s worth of physical labor. They approached the surrounding farming villages as learners seeking to change their own urban lives, not as ‘teachers’ trying to change others. And, most importantly, they offered of themselves freely and received from others with gratitude and humility.

Most learning is experiential anyway, isn’t it? We hardly get to pick and choose the lessons life teaches us.

The formal education system we have today was historically designed for the industrial economy. The public schools – which serve the university elite – emerged in the 1800s and reached their zenith in the 1950s. In the old days, education was one-size-fits-all. Schools have since been steeped in history and static knowledge; they fail to capture the here-and-now and to prepare us for contemporary society and the emerging issues of our time.

The Venezuelan Ministry for the Development of Human Intelligence enacted a series of programs and projects in the 1970s and ‘80s to improve its educational system and expound upon each person’s individual strengths and talents. These programs were offered for people of all ages – from birth to elderly age. By employing every available resource and reaching out to people across the nation, from the farms and rural areas to urban communities, the Venezuelan government promoted life-long learning for people of all ages and socio-economic backgrounds. Our nation is now slowly awakening to the educational needs of our times as we slip further behind on the global scale. President Obama is urging all Americans to seek higher education. But we must also take into account the radical changes that need to be made for college degrees to actually be considered valuable, and also to ensure that the disadvantaged peoples of the United States receive equal opportunities and ease of access to tools that can change their communities and their lives. Encouraging creativity through government programs, such as Venezuela has done, may be a starting point.

We also need to get honest about what ‘education’ really means. We either need educational reform in order to promote individual freedoms and the pursuit of happiness, or admit that school is designed to produce faithful, obedient citizens for jobs that require little more than technical skill and de-emphasize originality in the workplace. (I’m guessing the latter won’t be too popular.)

If you’re interested in learning more about the Shikshantar movements, check out their website at www.swaraj.org/shikshantar. The site has a huge database of alternative schooling-related articles that go into much more detail and propose a variety of future frameworks for societal learning.

Wednesday, November 4, 2009

Eat, Pray, Love by Elizabeth Gilbert

We women all know it but hate to admit it: Oprah Winfrey is the American goddess.

I confess: I read her book club recommendations verbatim. And they’re usually excellent reading. But not this one.

After a sticky divorce (aren’t they all?), writer Elizabeth Gilbert sets sail across the world to re-discover herself and achieve spiritual epiphany, including a several-month stint at an ashram in India.

I don’t see why she bothered to be in India, anyway, as she befriended a Texan and bemoaned all her crises to him the whole time she was there. And it’s not like you can’t wake up at 3AM and practice yoga in the States, if you really had any willful inclination to “find God”, or whatever Gilbert prattled on about ninety percent of the time. The other ten percent was her sobbing and occasionally shouting to the heavens at the injustice of it all. Oh, and there were some little bits about “seeing a blue light” and being filled with “blue energy”, which apparently cannot be found in America, because, you know, God isn’t here. Or maybe he/she/it is, but he/she/it is green. Or yellow. Or pink. Or something.

To be marketed as a ‘travel’ book is an utter lie. Rarely does the reader get to stop and enjoy the scenery. Rather, one is subjected to the endless nauseating rants and raucous outbursts of the author.

If you’re looking for a pat-on-the-back-reassurance that the world is okay, that the universe falls into perfect order, and that everything is going to be just fine, complemented by some one-dimensional sex and so-called ‘friendships’, then this is the book for you.

If you are actually interested in learning about India, then you will learn nothing from Gilbert.

Sadly, you will learn an unfortunate truth about Indo-American relations with regard to the phenomenon of American recreational travel.

I am disappointed by the number of people I meet who have been to India, and then manage to return and know next to nothing about the place. They complain about the music, the food, the poverty, the traffic, on and on. They can’t string two words together of a language other than their own. They have learned nothing new; they have no appreciation for where they’ve just been. They, like Gilbert, traveled to India with their own agendas, with preconceived notions about the way India should be; about the way the world should be. In return, they end up either disappointed or permanently clueless.

Gilbert is in the permanently clueless category.

Joothan by Omprakash Valmiki

I have a standing joke, if there is such a thing, with one of the customers that comes into the restaurant every Saturday night where I work. He asks if I’ll be in church tomorrow, and I always reply with some stupid one-liner or another. And perhaps, after awhile, I am a little afraid that the roof will collapse if I go.

But several weeks ago I went to a Sunday service. Don’t get the wrong impression; I didn’t pay attention to the sermon, of course. The organ’s tones were deafening and the crowd of people rising and lowering at arrhythmic intervals might have been distracting if the lighting in the balcony hadn’t been so perfectly conducive to getting lost in thought.

Omprakash Valmiki’s Joothan is a collection of memoirs of his life as a Dalit shortly after India won its independence from Great Britain. Though untouchability was indeed outlawed in the country’s constitution (an untouchable, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar, provided the document’s framework), Valmiki demonstrates in heartbreaking detail the prejudice and injustice that still prevails. And yet, up until that day, nothing had very deeply stirred me about this book.

Hunched over the book’s final pages in the last pew of the sanctuary, I discovered it. It was a little sliver of a line, nearly ten pages from the end, that brought the story full circle for me, and it was all hinging on this single, unintentionally poignant axis. It wasn’t even about an event that had happened in the author’s life, but rather a curt blurb about a Maharashtra community of Dalits sacrificing a child in order to persuade the gods to bless them with enough grain to survive another year.

I was suddenly and irrevocably grateful for my little brother sitting next to me, for being born into a country with an (at least supposedly) non-discriminatory public education system, for being able to eat dinner at a table every night. Or every other night. Or, okay, maybe I can’t remember the last time I ate dinner at a table, but it was dinner nonetheless. These things, which I’ve taken for granted on far too many occasions, now came crashing into perspective at once. I was filled with a sort of joy and despair all at once, a ‘malegria’, if you will. I handed my brother a relatively squashed Tootsie Roll from my purse and volunteered for the community CROP Hunger Walk the next week.

Maybe, I think, it’s these small gestures that count the most.

The White Tiger

I’m not usually a fan of Booker Prize winners. Originality, I think, does not always equal quality. When I first started getting into it, I thought, if it weren’t for the story taking place in India, I wouldn’t be reading this crap. But then, I couldn’t help it. As you read, the story becomes progressively more and more strange, wild, and darkly enticing, keeping you on the edge of your seat because you can never quite trust Balram Halwai, the “White Tiger”. He’s everything to love and hate about India. He’s corrupt and cynical and clever and cunning. He’s

chaotic and consummate, charismatic and celeritous. All those C’s.

The story is written as a series of seven letters to the Premier Wen Jiabao of China, beginning with the birth of a no-name boy in the small village of Laxmangarh, near Bodh Gaya, where the water buffalo is the head of the family and the townsfolk are forever at the mercy of crooked and dispassionate landlords. The tale progresses as Balram rises to the status of a Bangalorean entrepreneur through methods of eavesdropping, nicknaming, cab-driving, and murder. It is a profound and unapologetic portrait of the political strife of contemporary India, an informal but striking dissertation on poverty and terrorism and sacrifice.

I used to be very judgmental of books like this – books with no righteousness, no morality. And then I read another little book called Letters to A Young Poet by Rainer Maria Rilke. He said something along the lines of, “Literary critics will have their day, but their opinions are determined by their times. You have to appreciate a writer’s work for what it is, for how it speaks to you.” And this, I think, is completely fair.

By the end of the book, I realized that I had grossly misjudged Adiga. Rarely does an author exhibit such prowess at displaying profound ethical insight without saturating his words with overt sentimentality.

Thank you, Mr. Adiga. Maybe now I will go back to Steinbeck with an open mind.

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

माफ़ कीजिये - Sorry!

Maaf kijiye!

So sorry for the lack of updates! Mid-term exams are in full swing. I will return to the blogosphere by next week with my usual vitality and enthusiasm.

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

डोला रे डोला

हाई डोला दिल डोला मनन डोला रे डोला

लग जाने दो नजरिया, गिर जाने दो बिजुरिया

बिजुरिया बिजुरिया गिर जाने दो आज बिजुरिया

लग जाने दो नजरिया, गिर जाने दो बिजुरिया

बांधके मैं घुँघरू

पेहेनके मैं पायल

हो झूमके नाचूंगी घूमके नाचूंगी

डोला रे डोला रे डोला रे डोला

हाई डोला दिल डोला मनन डोला रे डोला

देखो जी देखो कैसे यह झांकर है

इनकी आँखों में देखो पियाजी का प्यार है

इनकी आवाज़ में हाई कैसी थानादार है

पिया की यादों में यह जिया बेकरार है

हाई, आई, आई आई आई आई

माथे की बिंदिया में वोह है

पलकों की निंदिया में वोह है

तेरे तो तन मनन में वोह है

तेरी भी धड़कन में वोह है

चूड़ी की छान छान में वोह है

कंगन की खान खान में वोह है

चूड़ी की छान छान में वोह है

कंगन की खान खान में वोह है

बान्द्खे मैं घुँघरू

हाँ पेहेनके मैं पायल

ओ झूमके नाचूंगी घूमके नाचूंगी

डोला रे डोला रे डोला रे डोला

तुमने मुझको दुनिया दे दी

मुझको अपनी हाँ खुशियाँ दे दी

तुमसे कभी न होना दूर

हाँ मांग में भर ले न सिन्दूर

उनकी बाहों का तुम हो फूल

मैं हूँ क़दमों की बस धुल

बांधके मैं घुँघरू

पहेनके मैं पायल

हाँ, बांधके मैं घुँघरू

पहेनके में पायल

ओ झूमके नाचूंगी घूमके नाचूंगी

डोला रे डोला रे डोला रे डोला...

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

गंगा - The Ganges

मैं उसकी माँ एक बच्चे के रूप में आपके पास आया,

मैं उसकी माँ एक बच्चे के रूप में आपके पास आया, mein uski maa ek bachcha ke hap mai aapka paas aaya,

I come to you as a child to his mother,

मैं तुम्हें एक अनाथ, प्यार से नम के रूप में आते हैं.

mein tumhein ek anaabh, pyaar se nam ke hap mai aale hain.

I come to you as an orphan, moist with love.

मैं तुम से शरण के बिना, पवित्र आराम के दाता.

mein tum se sharnna ke bhina, paweer aaram ke data.

I come without refuge to you, giver of sacred rest.

मैं तुम से एक आदमी आ गिरा, सभी के अंत्योदय,

mein tum se ek aadmi aa gira, sabhi ke antodaya,

I come a fallen man to you, uplifter of all,

मैं रोग से आप को पूर्ववत आया, सही चिकित्सक,

mein reg se aap ke puviivat aaya, sahi chikitsak,

I come undone by disease to you, the perfect physician,

मैं आ गया, मेरा दिल प्यास से सूखे, तुम, मीठी शराब के सागर,

mein aa gaya, sera dil pyaar se sukhe, tum imith sharab ke sagar,

I come, my heart dry with thirst, to you, ocean of sweet wine.

मेरे साथ क्या तुम जो भी होगा

mere sabh kya tum jaye bhi hega.

Do with me whatever you will.

These are the words of the Ganga-Lahiri (गंगा लाहिड़ी), or Waves of Ganga, a famous poem by 17th century Brahmin (ब्राह्मण) poet Jagannatha (जगन्नाथ). Jagannatha broke the laws that forbade upper-caste Brahmins from consorting with lower castes when he fell in love with a Muslim girl. Though he tried to explain the transcendence of love to his elders, he was exiled from his pious Hindu community. He then traveled to Varanasi, India's most sacred city, and sat along the ghats of the Ganges river. Perched on the 52nd step, he composed 52 verses dedicated to the river. The story goes that with every line, the Ganges rose a step, finally consuming him at the end of his final verse.

The allegory of the Ganga is a beautiful myth indeed, but it is so long that I will have to dedicate a separate post to it. The Ganges river is a symbol of purification, womanhood, motherhood, and guardianship. Devout Hindus believe that bathing in the Ganges will wash away their sins, and that if one's body is cremated on her banks he will break the karmic cycle and escape the world's suffering.

Unfortunately, the river is facing a crisis of pollution. (These days, do you expect anything otherwise?)

The 1,560 miles of the Ganges run through one of the most densely populated regions in the world. Over one-third of all Indians (think: all the people in America) live along the river in the Gangetic Basin. Most people do not have sewage or sanitation facilities, meaning that millions of gallons of raw sewage are dumped into the sacred river each day.

The Ganges Action Plan, launched in 1985, was an ambitious attempt to clean up the river. But it was poorly executed and resulted in failure. The Ganges is now nearly twice as polluted as it was twenty years ago. In addition, a recent government audit discovered that corrupt officials had long been siphoning off funds from the project.

It look as though it will likely be a while before the river goddess' waters are as clean as Hindu pilgrims believe them to be.

Monday, October 12, 2009

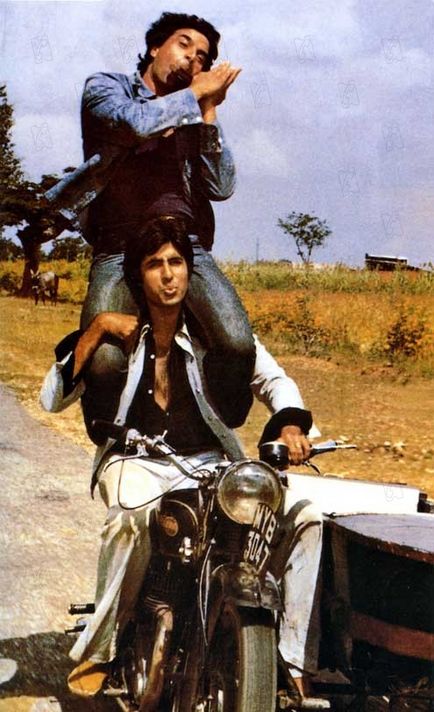

यह दोस्ती - Yeh Dosti (This Friendship)

Fortunately, though, the songs are great fun, and also a much better tool for learning Hindi than rote memorization. Check out this clip from Sholay: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ck77d3joH6I. The song was immensely popular at the time, and it's still impossible to listen to it without smiling.

(And hey, if you're a particularly observant American movie-goer, you might recognize the actor Amitabh Bachchan as the celebrity that gaved Jamal Malik an autograph in 'Slumdog Millionaire'.)

Here I've translated the lyrics as best I can:

यह दोस्ती हम नहीं तोडेंगे

yeh dosti hum nahin todenge

(We will not break this friendship)

तोडेंगे दम मगर तेरा साथ न छोडेंगे

todenge dam magar tera saath na chhodenge

(I may break my strength, but I will not leave your side)

ऐ मेरी जीत तेरी जीत, तेरी हार मेरी हार

ae meri jeet teri jeet, teri haar meri haar

(Hey, my victory is your victory, your loss is my loss)

सुन ऐ मेरे यार

sun ae mere yaar

(Hey, listen my man!)

तेरा ग़म मेरा ग़म, मेरी जान तेरी जान

tera gham mera gham, meri jaan teri jaan

(Your sorrow is my pain, my life is your life)

ऐसा अपना प्यार

aisa apna pyaar

(That's how our love is)

जान पे भी खेलेंगे, तेरे लिए ले लेंगे

jaan pe bhi khelenge, tere liye le lenge

(I'll even risk my life, for you I will)

जान पे भी खेलेंगे, तेरे लिए ले लेंगे

jaan pe bhi khelenge, tere liye le lenge

(I'll even risk my life, for you I will)

सब से दुश्मनी

sab se dushmani

(Become enemies with everyone)

यह दोस्ती हम नहीं तोडेंगे

yeh dosti hum nahin todenge

(We will not break this friendship)

तोडेंगे दम मगर तेरा साथ न छोडेंगे

todenge dam magar tera saath na chhodenge

(I may break my strength, but I will not leave your side)

लोगों को आते हैं दो नज़र हम मगर

logon ko aate hain do nazar hum magar

(People see two of us, but)

देखो दो नहीं

dekho do nahin!

(look, we are not two!)

अरे हो जुदा या खफा ऐ खुदा है दुआ

arre ho judaa ya khafa ae khuda hai dua

(Arre, that we be separated or angry, oh God I pray)

ऐसा हो नहीं

aisa ho nahin

(that this will not happen)

खाना पीना साथ है

khana peena saath hai

(We will eat and drink together)

मरना जीना साथ है

marna jeena saath hai

(We will die together)

साडी ज़िन्दगी

sari zindagi

(for the rest of our lives)

यह दोस्ती हम नहीं तोडेंगे

yeh dosti hum nahin todenge

(We will not break this friendship)

तोडेंगे दम मगर तेरा साथ न छोडेंगे

todenge dam magar tera saath na chhodenge

(I may break my strength, but I will not leave your side)

तोडेंगे दम मगर तेरा साथ न छोडेंगे

todenge dam magar tera saath na chhodenge

(I may break my strength, but I will not leave your side)

Conversational Hindi - Lesson 2

bahumat ki aawaj nyaya ka gheitak nahi hai.

aanyay mei sahayeg dena, aanyay ke hi samaan hai.

To cooperate in injustice, injustice is the same.

Friday, October 9, 2009

Conversational Hindi - Lesson 1

I thought that it would perhaps be interesting to start a series of posts on conversational Hindi. There are a few sites on the internet that teach Hindi vocabulary, but seem to overlook the wonderfully unique way of phrasing things that Indians have. You can study Hindi grammar and vocabulary for days, months, even years - but never be understood by native speakers, only because you cannot literally translate English sayings into Hindi sayings.

I thought that it would perhaps be interesting to start a series of posts on conversational Hindi. There are a few sites on the internet that teach Hindi vocabulary, but seem to overlook the wonderfully unique way of phrasing things that Indians have. You can study Hindi grammar and vocabulary for days, months, even years - but never be understood by native speakers, only because you cannot literally translate English sayings into Hindi sayings.This YouTube video does a good job of noting the difference between the ways that Hindi is spoken versus written.

There are three main variants of Hindi in India. First is Hindi proper, which is the official language of India and uses lots of Sanskrit loanwords. Secondly, there is Urdu, which is practically indistinguishable from Hindi aside from three important differences: Urdu uses the Persian-Arabic script, uses lots of Persian-Arabic loanwords, and it is mainly used by Muslims in the northwestern states and Pakistan. Thirdly, there is Hindustani, which is a neutral blend of the two. It is used in regular, informal speech. The standard dialect of Hindi is Khariboli.

That's all for today! Don't worry if you cannot read the Devanagari script for now. I think it will be easier to understand it if you know how to say a few things in Hindi first, just as a child learns to speak a few words before learning to read.

Indian Ayurveda can help reverse American obesity epidemic

Our supersized portions have taken a toll on our health: among the top five leading causes of death in America are heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes - all related to obesity.

I can barely make a - pot? pan? - of spaghetti, but my aunt - who works in the food industry - persuaded me to go with her to Jackson Heights, New York to learn about Ayurveda (using food as a medicine) with a group from the Institute of Culinary Education. I knew that all the money raised goes toward a good cause (educating widowed child brides in India), but I was still suspicious.

I used to have some pretty bizarre notions about people who practice ayurvedic 'medicine' - I envisioned a group of hippies smoking pipes, singing, dancing, and just generally swept up in a blind mockery of Indian values and spirit, the way most Indian culture is interpreted in the west. I envisioned a cult-like scene like 'Dum Maro Dum' from 'Hare Rama Hare Krishna' (Dev Anand, 1971). But then again, I manage to make pancake batter into rocks, so what do I know?

Mr. Subrato Bhattacharya, travel consultant, photographer, and food stylist for the United Nations (quite a job description, eh?) was our foodie guru and lent some insight into the difference between Indian and American diets.

"Ayurveda is an ancient Indian science and art," Bhattacharya explained. "The word 'ayurveda' literally means 'body knowledge'."

Ayurveda uses food as a medicine to enhance energy, improve complexion, clear the senses, strengthen vocal power, add longevity, lighten mood, nurture the spirit and increase physical stamina.

"You are what you eat. Our body and the earth are made up of the same components. Put simply, the body is just a byproduct of food," he clipped.

There are two concepts of cooking in ayurveda: consuming a balanced combination of earth elements to create a balanced chemical reaction from the body. Our American diet generally promotes negative imbalance. For example, dipping chicken nuggets in honey mustard sauce may cause loss of vision, trembling, and lowered IQ. Drinking milk with fruit may cause acidity and stomach upset.

Why is this?

"Every person is born with a certain balance of wata, pita and kapha in their bodies," says Bhattacharya. "Wata - meaning air, pita - meaning energy, and kapha - propensity to illness."

Different foods can alter the balance of wata, pita and kapha. Beans, for example, are a wata-pita food. Milk and dairy are kapha foods. Fresh meat, fruit, and vegetables - once living elements of nature - are energizing, pita foods and provide much more nutrition than processed foods.

"Please, I beg you, do not eat processed foods," Bhattacharya pleaded. "They do no good. You will become very vulnerable to sickness and disease."

Most American foods are high in fat and calories, but low in nutritional value. We eat irregularly, at odd hours, and in huge quantities. It is difficult to break the cycle that is so grounded in the culture. We skip breakfast, snack through lunch, and then finally eat a big meal right before bed. We are too isolated and busy to care. There just isn't any specific time that we can call meal-time.

But is the pot calling the kettle black? Perhaps feeling too overwhelmed to eat properly is just a symptom of inefficient nutrition.

You don't have to learn Indian cooking to learn the lessons of ayurveda. Just listen to your body and be sensible about its needs. Don't try to assess your dietary needs with numbers on a scale - think about your emotions. Feeling a little down? Perhaps some pita foods, like a salad or turkey sandwich will help. Mad at the world today? Try some yogurt or cheese. Hopefully with practice, discipline, and time, we will come to appreciate our bodies for what they are - moving structures of energy - and the 'battle against the bulge' will end.